Discover the art, ideas, and world of M.C. EscherWho is M.C. Escher?

Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898–1972) was a Dutch graphic artist with a watchmaker’s discipline and a magician’s timing. He worked in reproducible media, woodcut, wood engraving, lithograph, and mezzotint, and used them to stage quiet revolts against common sense. Staircases fold back into themselves. Water pours downhill and somehow arrives higher than where it started.

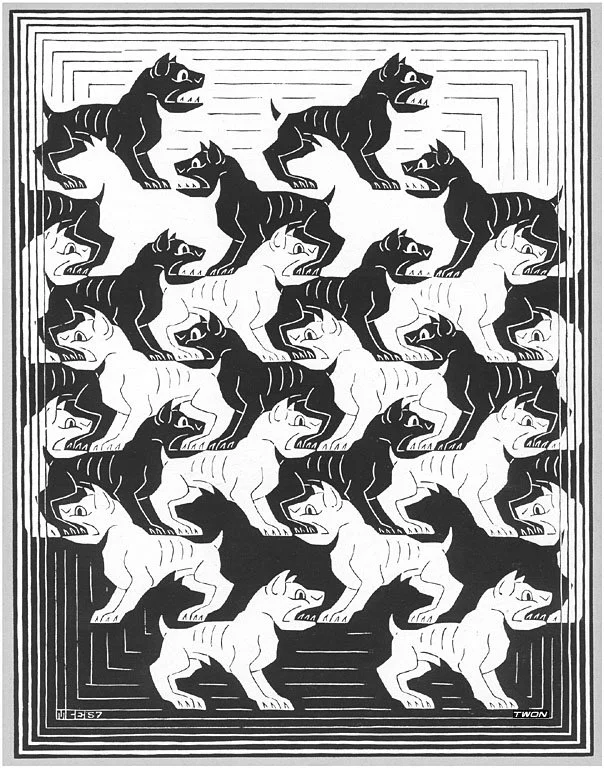

Birds and fish slip past one another until the picture becomes nothing but the logic that binds them. M.C. Escher’s trick isn’t dreaminess; it’s exactness. Every brick is shaded, every hand articulated; each small portion is right, which is why the whole can afford to be impossible.

M.C. Escher belongs to that thin line of artists who become adjectives. “Escher-like” has nothing to do with palette or brushstroke; it means a structure that obeys its own rules so ruthlessly that your brain finally agrees to believe it. Mathematicians love him for that; designers love him for the clarity; children love him because their eyes get the joke before anyone explains it. If you’re here to meet Escher the artist, you’re meeting a draughtsman who thought like an engineer and drew like a realist, and who, by staying faithful to the local truth of each line, made global contradiction look inevitable.

What is M.C. Escher famous for?

M.C. Escher is famous for prints that merge mathematical precision with visual paradox. His work features impossible architecture, infinite staircases, waterfalls that defy gravity, and tessellations, patterns that fill a surface perfectly, often with animals or human figures that transform into one another. Pieces like Relativity, Drawing Hands, and Sky and Water I made him an icon for art that makes you question the rules of space and perception.

Who is Mr. Escher?

“Mr. Escher”, as the English and American media loved to refer to him as, was a Dutch graphic artist born in 1898 in Leeuwarden, in the north of the Netherlands, the youngest of five sons of a civil engineer and a mother who ran the household with quiet efficiency. He grew up in a culture where neatness mattered. He wasn’t a standout student. He failed a couple of subjects, muddled through others, and was openly bored by anything that didn’t involve drawing or some sort of pattern. He drew constantly. Not languid art-school sketches: careful, measured drawings that tried to get things right. He also had the kind of mind that notices hinges and stair-tread ratios and how bricks overlap.

He went to the School for Architecture and Decorative Arts in Haarlem and did what sensible people expected: he started in architecture. It lasted months. His drawing teacher, the printmaker Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita, saw what the boy could do with a gouge and a burin and how naturally he thought in terms of planes and reversals, the very grammar of printmaking. Escher switched tracks. It wasn’t a romantic leap; it was an alignment. Architecture gave him structure; printmaking gave him a laboratory where structure could be multiplied.

Escher in Italy

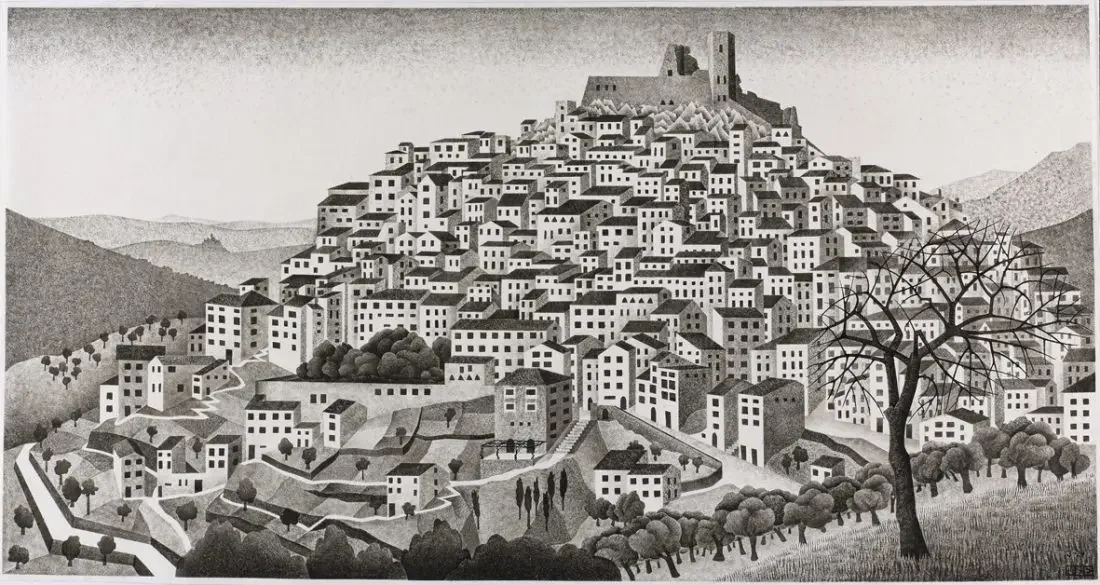

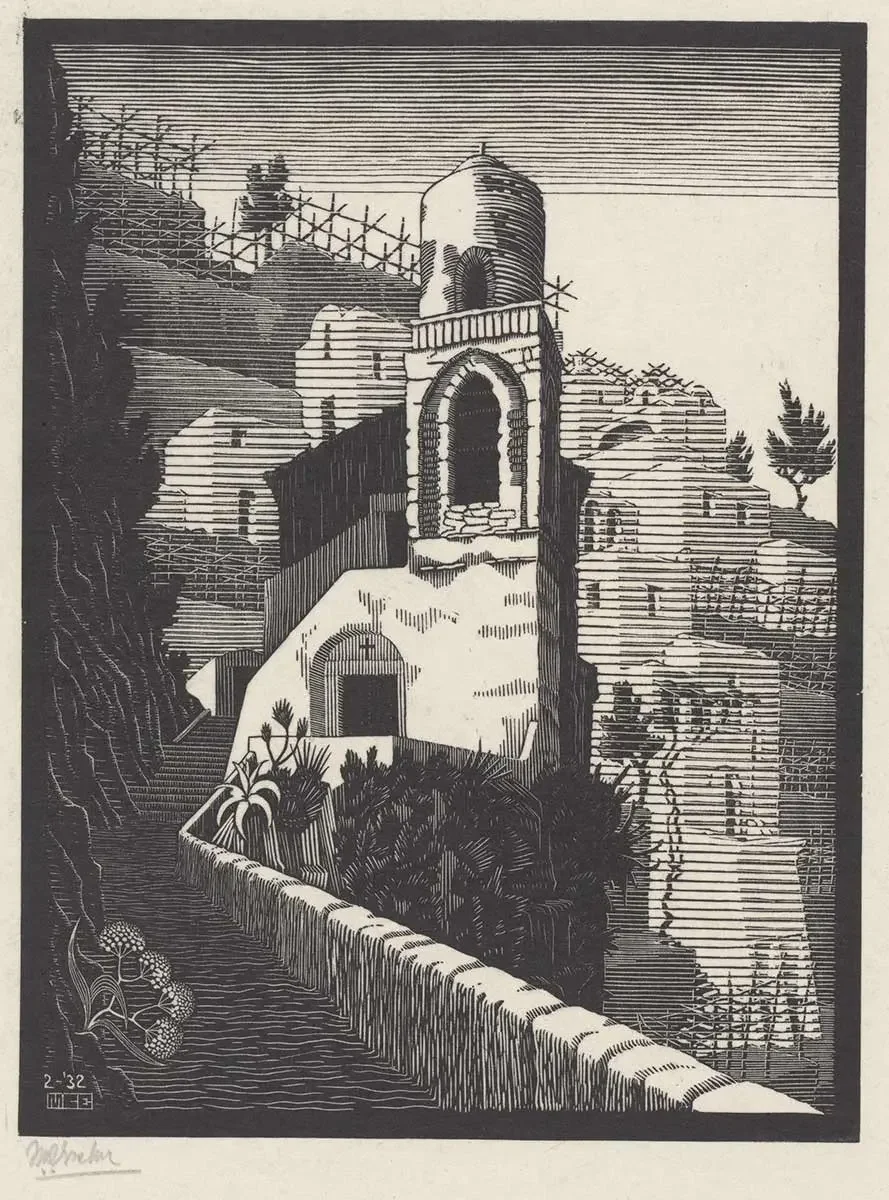

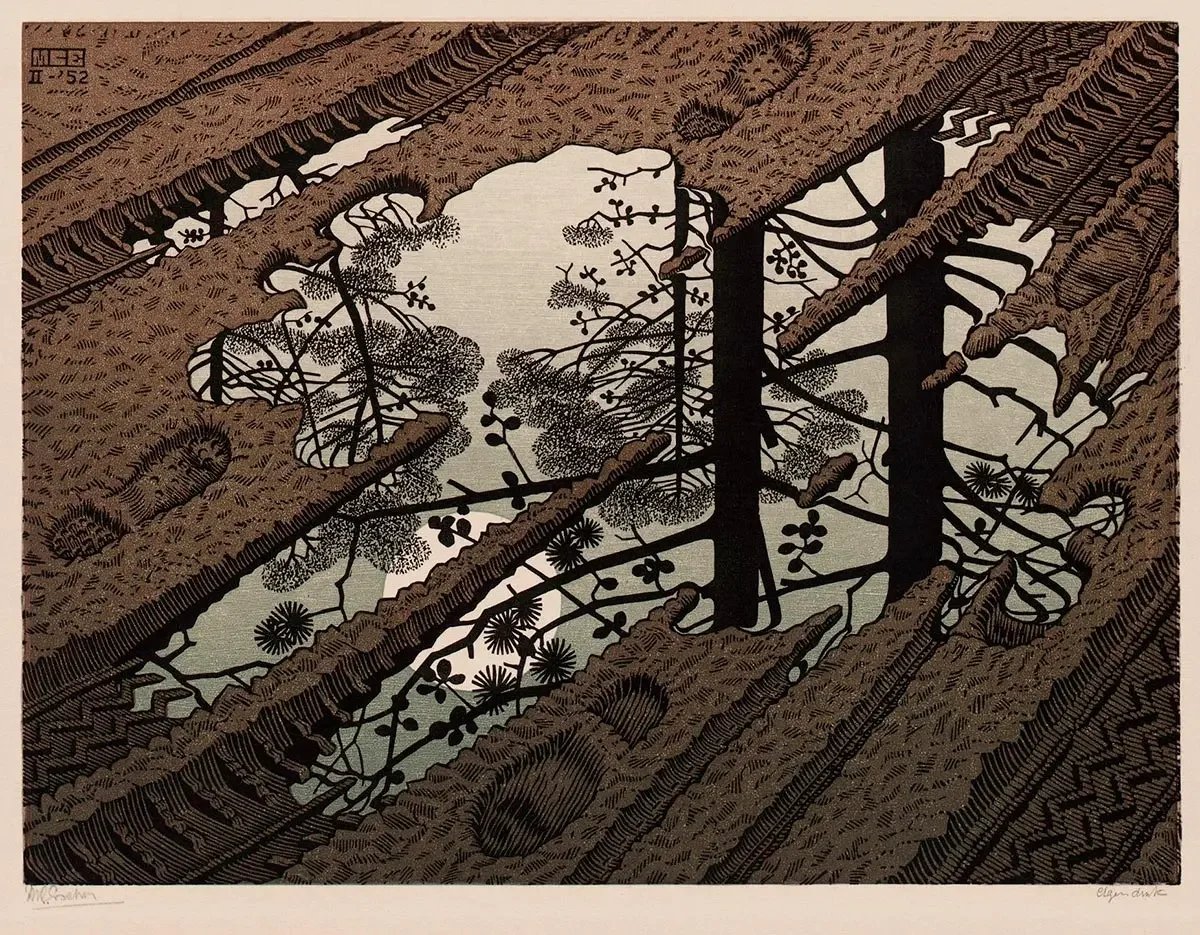

He finished his studies in 1922 and moved through a clutch of decisive years like a man collecting tools. He saw Italy, and Italy saw him back. Ruins and arches, tight stairwells, cloisters, colonnades, the built environment became a sketchbook full of premonitions. In 1923, he settled in Rome. He married Jetta Umiker the next year. They made a life. He walked and sketched, filling folios with streets and courtyards and steps that didn’t yet contradict themselves. He made moody woodcuts of hill towns and beautiful mountainside views. The technical interest is visible even here; he’s already solving for joinery, for how one plane becomes another.

Escher’s travels to Spain

But the most important pilgrimage happened along another axis, south to Granada in Spain. At the Alhambra, he found walls that behaved like mathematics: nonfigurative tilings that fill the plane without gaps or overlaps, running indefinitely in all directions. He copied them by hand. It wasn’t inspiration; it was training. He did it again on a second trip. Then he did the only thing that would make those patterns his: he replaced the abstract tiles with living figures: fish, birds, lizards, human profiles that locked together. The discipline of the tiling remained; the content changed. In that pivot, you can hear his whole career click into place.

The 1930s and World War II

He and Jetta stayed in Italy until the mid-1930s, moving north again as politics curdled. There was a brief Swiss interlude; then Belgium; then the Netherlands for good. The change in setting coincided with a clean tightening of the work. Landscape prints receded. In their place came images constructed like proofs: transformations where one thing becomes another by steps so smooth you feel you’ve missed the turn; reflections where a mirrored sphere compresses a whole room cleanly onto a palm; self-reference where the drawing draws itself. World War II had a tremendous impact on the artist, with very few works being produced due to a ban by the Nazi government. Escher himself barely survived, nearly dying of starvation in the Dutch famine of 1944-1945.

Geometry and the 1950s

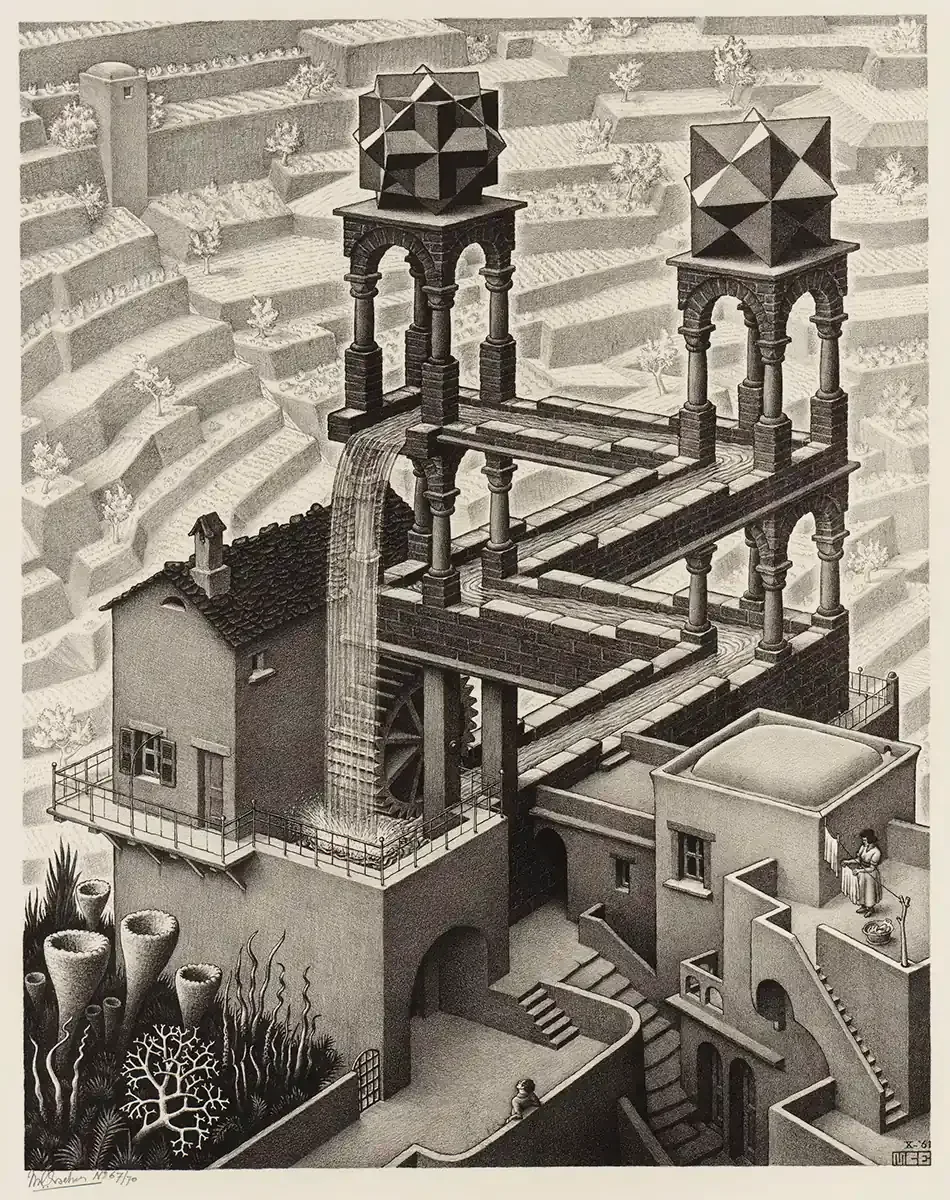

The 1950s brought him into contact with mathematicians who saw their ideas, suddenly made visible, in his pictures. He absorbed new toys, most famously the Penrose triangle (a coherent impossibility that became the engine of Waterfall) and the stairs that double back (Ascending and Descending). He also took a serious interest in hyperbolic geometry and the way a pattern can accelerate toward a boundary while forever running out of room, a sensation he made tangible in the Circle Limit series. He became, without trying, an ambassador between disciplines: the artist who could make difficult talk look like something.

How did M.C. Escher die?

M.C. Escher died on 27 March 1972. He had been ailing for years, as early as the 1960s. However, he kept working, producing plenty of art in his final years. He moved to the Rosa Spier House in Laren, a home for artists, where he could have a studio on the premises.

Escher worked in reproducible media because he liked the control: you carve, you ink, you press, you learn. You can pull several states and improve the plate or block while testing the result. The materials suit his mentality.

Woodcut & wood engraving gave him crisp borders, firm rhythm, and the ability to repeat and transform motifs with exact edge control.

Lithograph gave him continuous tones and the depth needed for rooms you can mentally walk around inside.

Mezzotint gave him rich blacks and velvet transitions, the right tool for a picture like Eye or any scene that asks for light to fall as weight, not line.

Read more about his art style

‘‘Snakes’’ is M.C. Escher’s final work. He completed it in 1969.

What was the impact of M.C. Escher?

Mathematicians embraced Escher because he gave them pictures of things they had long discussed in symbols: symmetry groups, hyperbolic plane models, and recursion. He didn’t preach their theorems; he made their phenomena visible. Architects and designers read the work as an argument for disciplined invention. Psychologists and vision scientists use the prints as clean cases for how perception reconciles conflicting cues. Teachers in art and math classrooms rely on them because students don’t need to be persuaded to care; their eyes have already started working.

And culture in general made room. Album covers, film sets, games, you know the list. But the pop afterlife isn’t the point. The work hasn’t survived because it’s cute; it has survived because it is useful and true to itself. The prints explain themselves; they solve a problem you didn’t know you had: how to see consistency inside contradiction.

More than optical illusions

But the medium is only the beginning. The reason people still care, and why “optical illusion artist” feels too small for him, is that he treated pictures like systems. He found a rule and then tested it to failure, or to the edge of failure, or to the place where the picture could continue forever if only the paper did.

Impossible architectures: rooms and staircases that make sense in every detail and refuse to make sense as a whole.

Tessellations: figures that tile the plane, not as decoration but as content, turning geometry into cooperation between silhouettes.

Transformations: long progressions where motif is destiny; words become pattern, pattern becomes creature, creature becomes city, city becomes something else again. Read all about this technique.

Reflections & spheres: curved spaces that fold the world back into itself with cool completeness.

Recursion & self-reference: hands drawing hands, galleries containing the picture you’re already viewing, loops that announce themselves like a magician revealing the secret while the trick continues to work.

A Longer Look at the Work

It’s useful to linger on a few pieces, not because they’re the only important ones, but because they show the full range of how he thought.

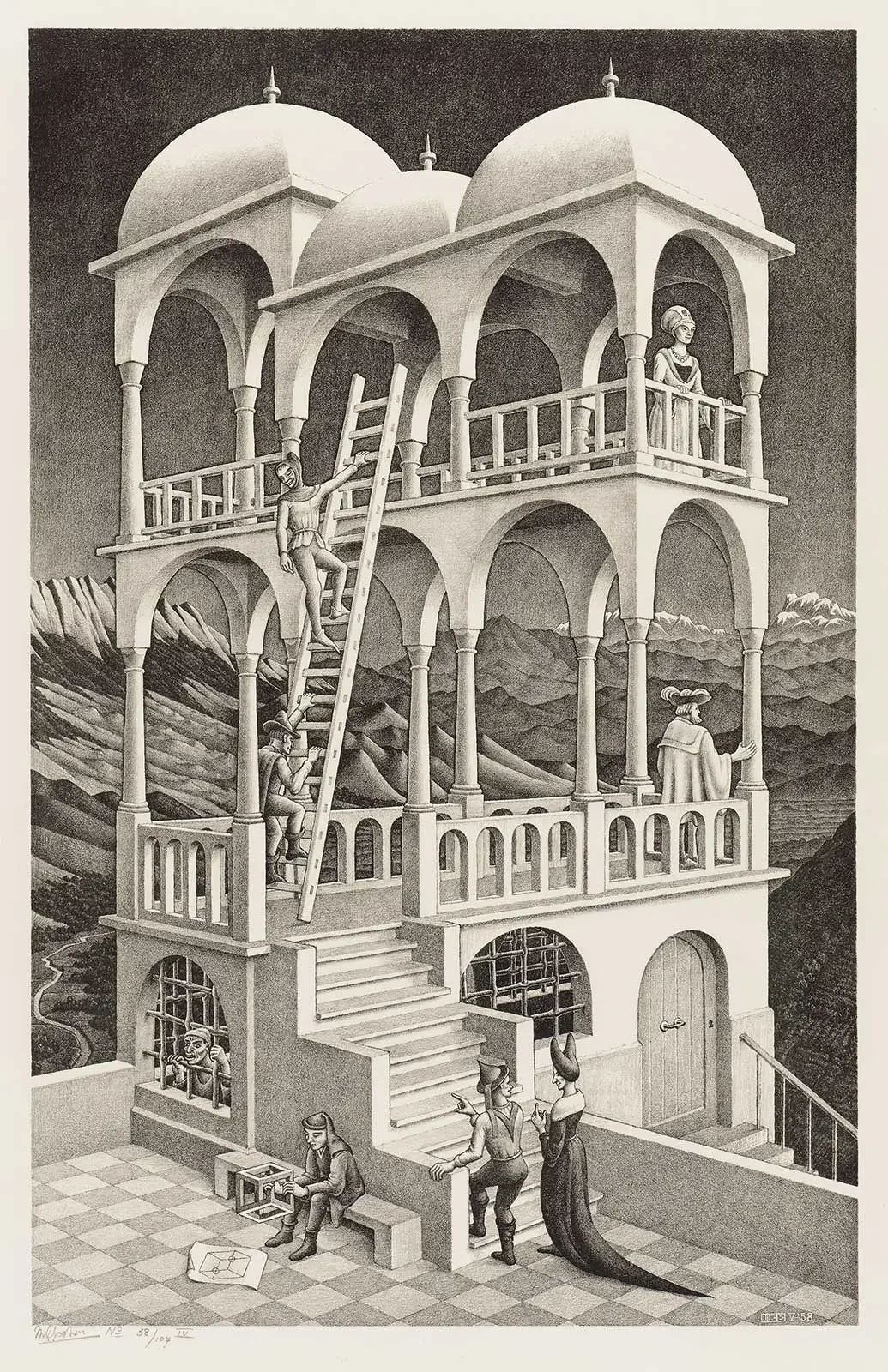

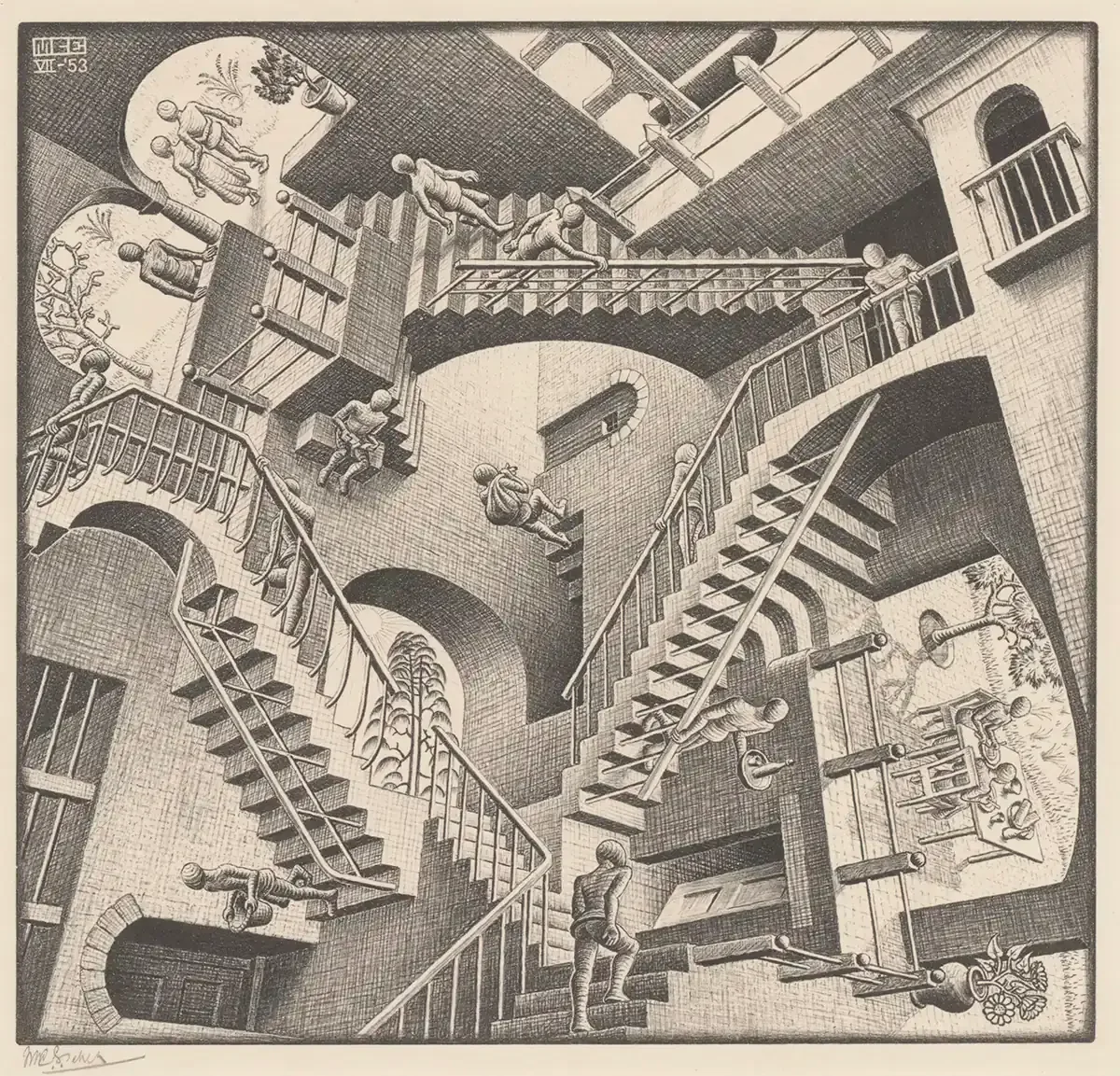

Relativity (1953) is a floor plan engineered to humiliate gravity. Multiple stair systems cross within a single building; people ascend and descend obedient to their own down. The picture explains itself in under a second, then keeps paying out as you track doorways, furniture, and the stubborn calm of the figures. The internal lighting is consistent within each gravity pocket; shadows behave; rails attach to walls that feel load-bearing. Every local truth is honored. That’s why the global contradiction pierces.

Read everything about Relativity.

Drawing Hands (1948) is what it says: a pair of hands drawing one another into being. It’s the plainest demonstration of recursion you can hope for and oddly touching, because the draftsmanship is so careful; each knuckle becomes a small portrait of attention. A lesser artist would spike the irony; Escher lets the premise sit and trusts the clarity.

Detailed breakdown of Drawing Hands.

Waterfall (1961) looks like an innocent aqueduct snaking down to a mill. Track the channel and you realize the water rises on its way to the drop, completing a loop that would run forever if the world permitted it. The trick is built from two Penrose triangles inserted in perspective so neatly that you can stare for minutes without finding a cheap seam. Once you see the impossibility, it doesn’t “break”; the illusion stabilizes at the paradox.

Sky and Water I (1938) is the cleanest lesson in figure/ground Escher ever made. On the left, white birds drift across a white field, the black ink only outlining them. On the right, black fish swim in a black field. In the middle, the edges that define bird also define fish; the mind can’t decide which to see first, and it enjoys not deciding. The pattern transforms without a single fuzzy step.

Go deep into the Sky and Water I.

Bond of Union (1956) builds two faces out of a single ribbon that rotates through space like a steady thought. There’s nothing impossible here. It’s simply spatial music: a form that remains itself while changing orientation, a quick answer to people who assume Escher only did tricks.

Belvedere (1958) plays a restrained game. No waterfalls, no stair loops, just a peaceful building where beams connect in ways that work perfectly in the picture and not at all in space. Look at the ladder; trace the bars; feel the certainty move in behind your eyes.

Three Worlds (1955) compresses a lake into three simultaneous realities: leaves floating on the surface; the reflection of trees above; a fish cruising below. It’s not a paradox, more a reminder that multiple constructions of reality can be true at once.

Reptiles (1943) is Escher’s private joke and a manifesto. Little lizards crawl out of a flat drawing, tramp across real-world objects, a book, a dodecahedron, a pack of matches, and march back into the paper, becoming pattern again. That’s what his prints do: walk into life, then snap flat and reveal the method.

Read everything about Reptiles.

Eye (1946) is a mezzotint where light becomes fabric, not line, and a skull hovers in the pupil like a warning you only catch after the beautiful scumble of tone has had its say.

Hand with Reflecting Sphere (1935) holds the whole room, the whole world, really, inside a palm, a self-portrait that doubles as a primer on curved perspective. The image is calm, contained, almost indifferent to its own brilliance.

How Did M.C. Escher Make His Art?

Escher’s process was anything but glamorous. It was methodical, faithful, and iterative. He began with study drawings, testing edges, and refining forms. He prepared blocks and stones, pulled proofs, corrected, and tried again. He wasn’t chasing lucky effects; he was constructing them. That’s why his finished prints carry such confidence: every excess stripped away, only what mattered left behind.

For a deeper dive into technique, how a woodcut differs from a wood engraving, how lithography creates tone, how mezzotint builds darkness, or why perspective grids mattered, you’ll find it on the Art Style page. You don’t need that knowledge to enjoy the images. But once you have it, the pleasure sharpens; you see where the craft ends and the audacity begins.