M.C. Escher Tessellations: A Complete Guide to Infinite Patterns

When people hear the name M.C. Escher, they often think of impossible staircases or gravity-defying buildings. Yet for Escher himself, tessellations were the cornerstone of his career. He began experimenting with them in the 1920s and never truly stopped, producing hundreds of drawings, prints, and sketches that explored the idea of covering a surface with repeating figures. Unlike the tiled floors and Islamic mosaics that first introduced him to tessellation, Escher’s patterns were alive. Birds soared, fish swam, lizards crawled, and angels fought with devils, all locked together in unbreakable harmony.

So, what exactly is an Escher tessellation? At its simplest, a tessellation is a way of filling space with shapes that leave no gaps and do not overlap. A bathroom floor of squares is a tessellation, as is a honeycomb of hexagons. But Escher was never content with pure abstraction. He discovered that those same rules could be bent and reshaped so that one polygon became a fish, another a bird, and together they produced not just a design, but a living narrative.

What are the most famous Escher tessellations?

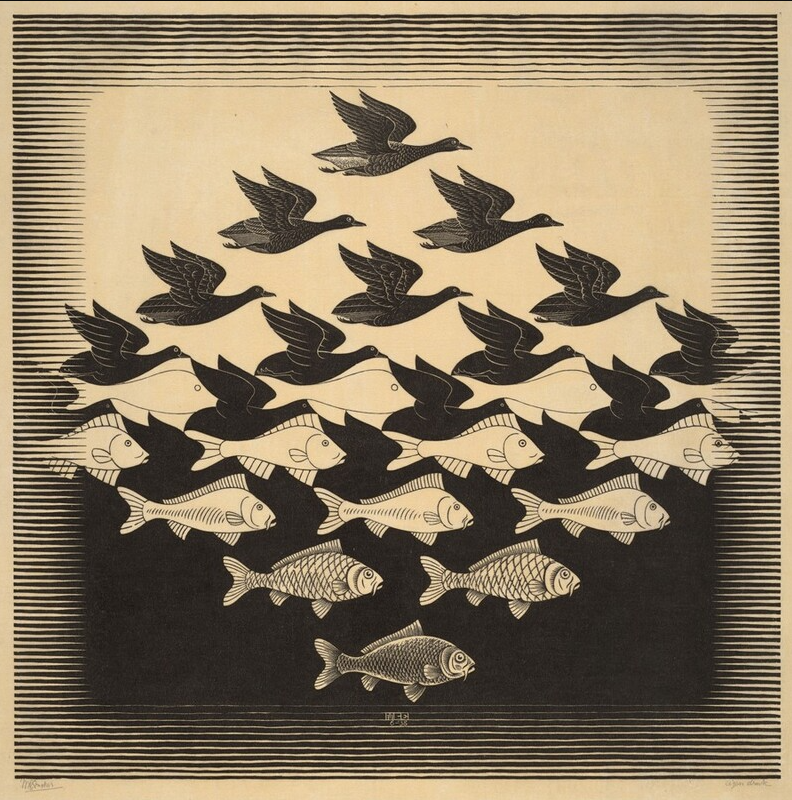

Certain works stand out as landmarks in his exploration of tessellation. Sky and Water I is perhaps the most widely reproduced. At the bottom of the print, rows of fish swim horizontally; at the top, birds fly across a pale sky. Between the two, the figures gradually change, the negative space of one becomes the positive space of the other, a perfect balance of black and white.

Another beloved piece is Day and Night, where two flocks of birds, one black and one white, emerge from a field of tessellated shapes and fly over mirrored landscapes. Escher often said he was fascinated by dualities, night and day, good and evil, order and chaos, and this print embodies that theme.

In Reptiles, the tessellation literally comes to life. Small lizards crawl out of a flat drawing, march across books and objects, and climb back into the paper. It is a witty, almost surreal commentary on the relationship between two dimensions and three, between the world of representation and the world of reality.

Then there are the great hyperbolic prints like Circle Limit III, which remain breathtaking demonstrations of infinite tessellation. Looking at them, one feels both awe and vertigo, as though peering into a world where order has no end.

Sky and Water I (1938). Woodcut.

Why does Escher use tessellations?

Escher’s fascination with tessellation began during a trip to Spain in 1922. Wandering the halls of the Alhambra in Granada, he was struck by the complex mosaics on the walls. Here was geometry in its purest decorative form: endless networks of stars, polygons, and curving vines, all repeating without end. Escher sketched obsessively and later admitted that the visit changed the course of his life. Back in the Netherlands, he began to experiment on his own, taking a square or hexagon and modifying its edges into curves that hinted at a wing or a tail. Once he had one shape, he repeated it across the page, and suddenly a flock of birds emerged, or a cluster of reptiles.

This process was deceptively simple, yet it allowed Escher to explore ideas far more complex than tiles on a palace wall. He became interested in how one figure could transform into another, how a fish could gradually become a bird, or how white space could turn into black space and back again. His art was less about the static perfection of pattern and more about the drama of transformation.

Predestination (1951). Lithograph.

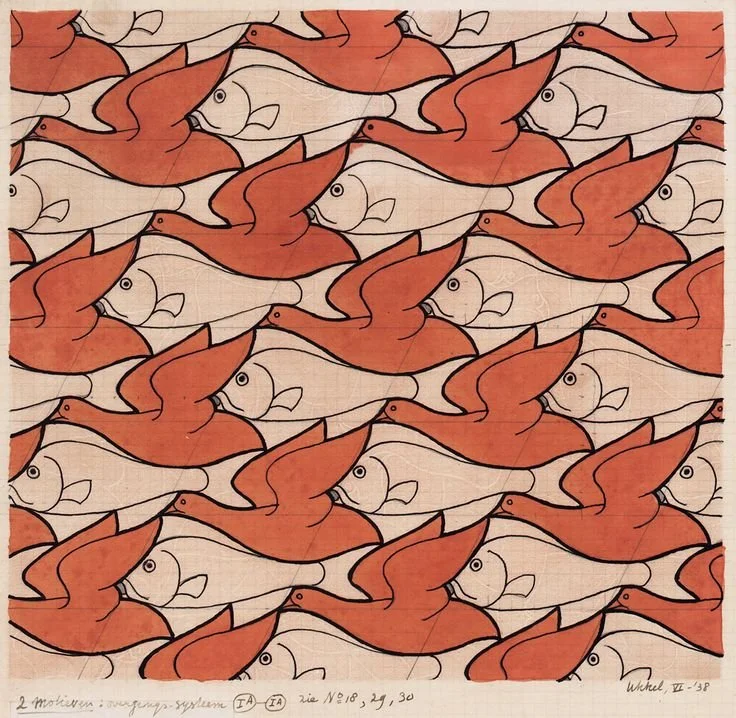

A sketch from Escher’s notebook (1938).

How did Escher make his tessellations?

Escher’s working method was painstaking. He often began with a simple polygon such as a square. By cutting and shifting parts of its edges, he reshaped the figure into the outline of an animal or person. Once satisfied, he would repeat the figure across the plane, testing whether the altered shape truly fit without leaving gaps. If it worked, he refined the design, adding scales, feathers, or faces until the tessellation looked both mathematically precise and artistically alive.

This mixture of rigor and imagination is what makes his tessellations so enduring. Anyone can draw a tiling of squares, but it takes an artist’s eye to see in those squares a school of fish, a flock of birds, or a regiment of soldiers. Escher’s notebooks reveal hundreds of experiments, some abandoned, some developed into famous prints, that show just how much trial and error was involved.

Escher worked primarily with Euclidean geometry, the flat, rule-based system of lines, angles, and polygons we all learn in school. He intuitively explored symmetry operations like rotation, reflection, and glide reflection, even before he understood the formal mathematics behind them. Later in his career, he expanded into hyperbolic geometry, where space curves toward infinity, producing works that astonished mathematicians for their accuracy despite Escher’s lack of formal training.

Who Is the father of tessellation?

M.C. Escher is often celebrated as the father of tessellation art. While tessellated patterns go back thousands of years, think Roman floor mosaics or the intricate tilework of Islamic architecture, Escher's tessellations did something entirely new. He transformed flat, repeating shapes into lively narratives, filling the plane not with abstract geometry but with birds, fish, and creatures that seemed to move, interact, and carry personalities of their own. Mathematicians might resist naming any single “father” of tessellation, since the concept long predates him, but Escher’s imaginative approach is what made tessellation a living art form in the modern imagination.

Escher working on a tessellation.

What is the math behind Escher’s tessellations?

Although Escher had no formal training in mathematics, his work brushed against some of its deepest areas. He quickly realized that tessellations were governed by rules of symmetry: you could repeat a shape by sliding it across the page, flipping it, or rotating it. By combining these operations, he could cover an entire plane without leaving gaps. In the 1920s, mathematicians had already classified all possible repeating patterns into what are called the seventeen “wallpaper groups.” Escher, discovering this on his own, tested nearly every one of them, filling notebook after notebook with intricate sketches.

Later in life, he pushed beyond flat geometry into more radical territory. Inspired by conversations with mathematicians such as H.S.M. Coxeter, he began to experiment with hyperbolic geometry — the mathematics of curved, infinite space. Prints like Circle Limit III show fish shrinking as they approach the rim of a circle, giving the impression of infinity contained within a finite frame. Escher himself admitted he did not fully understand the mathematics behind these ideas, but his intuition was astonishingly accurate, and mathematicians later marveled at the precision of his visualizations.

A section of Metamorphosis featuring tessellation. 1938, woodcut.

Why Tessellations Matter

For Escher, tessellations were more than decorative tricks. They were a way to explore fundamental ideas: the tension between order and chaos, the transformation of one form into another, the concept of infinity. They also allowed him to connect two worlds often kept apart: mathematics and art. Mathematicians admired him for visualizing abstract concepts, while the general public loved him for the sheer beauty of his images.

The cultural reach of these works has been extraordinary. His tessellations appear in textbooks, on album covers, in advertisements, and in the work of contemporary designers. They are instantly recognizable and endlessly imitated. The term “Escher tessellation” has itself become shorthand for any repeating pattern of interlocking figures.

How do I start collecting Escher’s tessellation prints?

Collecting Escher’s tessellation prints is one of the most exciting pursuits in the art market. Because his tessellations are among his most iconic works, they remain highly sought after by collectors worldwide. Original woodcuts and lithographs regularly appear at auction, often selling for tens of thousands of euros. A well-preserved impression of Sky and Water I, for example, might reach around €20,000.

With such demand comes risk. Escher’s popularity has produced a flood of reproductions, posters, and unauthorized prints. Authentic works are typically signed in pencil “MCE” and numbered within their edition, and provenance is essential. Serious collectors usually buy through major auction houses or trusted specialist dealers.

For many, the value goes beyond money: owning an Escher tessellation print means holding paper that once passed through his press, and witnessing firsthand the extraordinary precision of his craft.

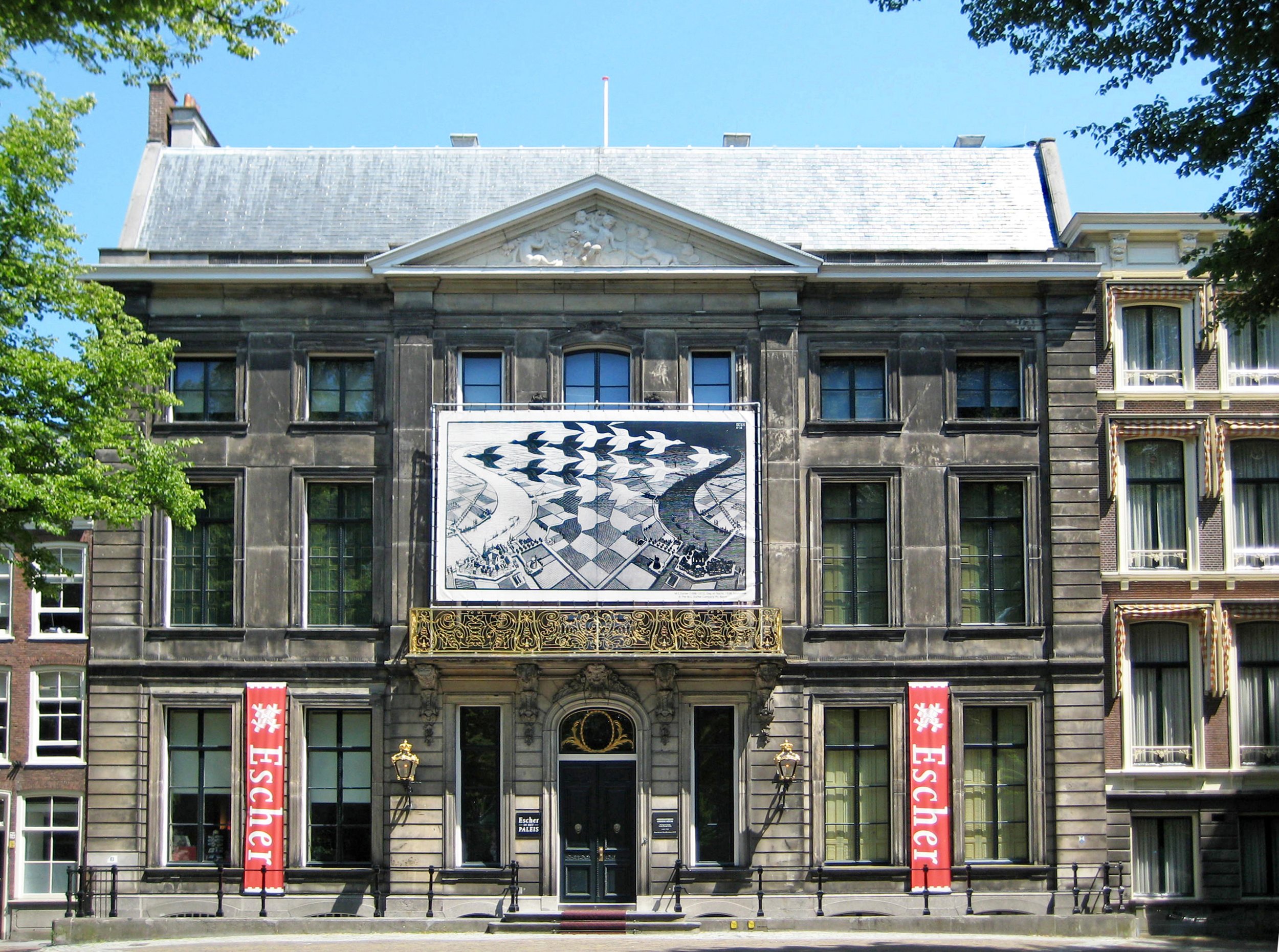

Where to See Escher Tessellations

The best place to immerse yourself in Escher’s tessellations is Escher in Het Paleis in The Hague, a museum devoted entirely to his work. Here you can see dozens of prints, sketches, and even the notebooks in which he worked out his tessellation experiments. Major museums such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. also hold significant collections, and traveling exhibitions bring his work to audiences around the world.