M.C. Escher’s Drawing Hands: The Artwork That Draws Itself

Before continuing, please take a moment to really look at the work.

Few artworks are as instantly recognizable, or as conceptually playful, as Drawing Hands by M.C. Escher. Two hyper-realistic hands emerge from a sheet of paper, each holding a pencil, each busily sketching the other into existence. The effect is so crisp and logical that you almost forget it’s impossible.

What is Drawing Hands by M.C. Escher?

Drawing Hands is a lithograph Escher created in 1948. The composition shows two hands, both life-sized and rendered in meticulous detail, extending from shirt cuffs that seem to emerge directly from the paper’s flat surface. One hand is drawing the cuff and fingers of the other, while that other hand is simultaneously sketching the first. The illusion is complete: each hand appears both as the creator and as the creation.

The piece sits firmly in Escher’s repertoire of “paradoxical” works, images that fold logic back on itself until the impossible feels inevitable. It’s one of his most reproduced works, often used as a visual shorthand for recursion, self-reference, or the paradox of creation.

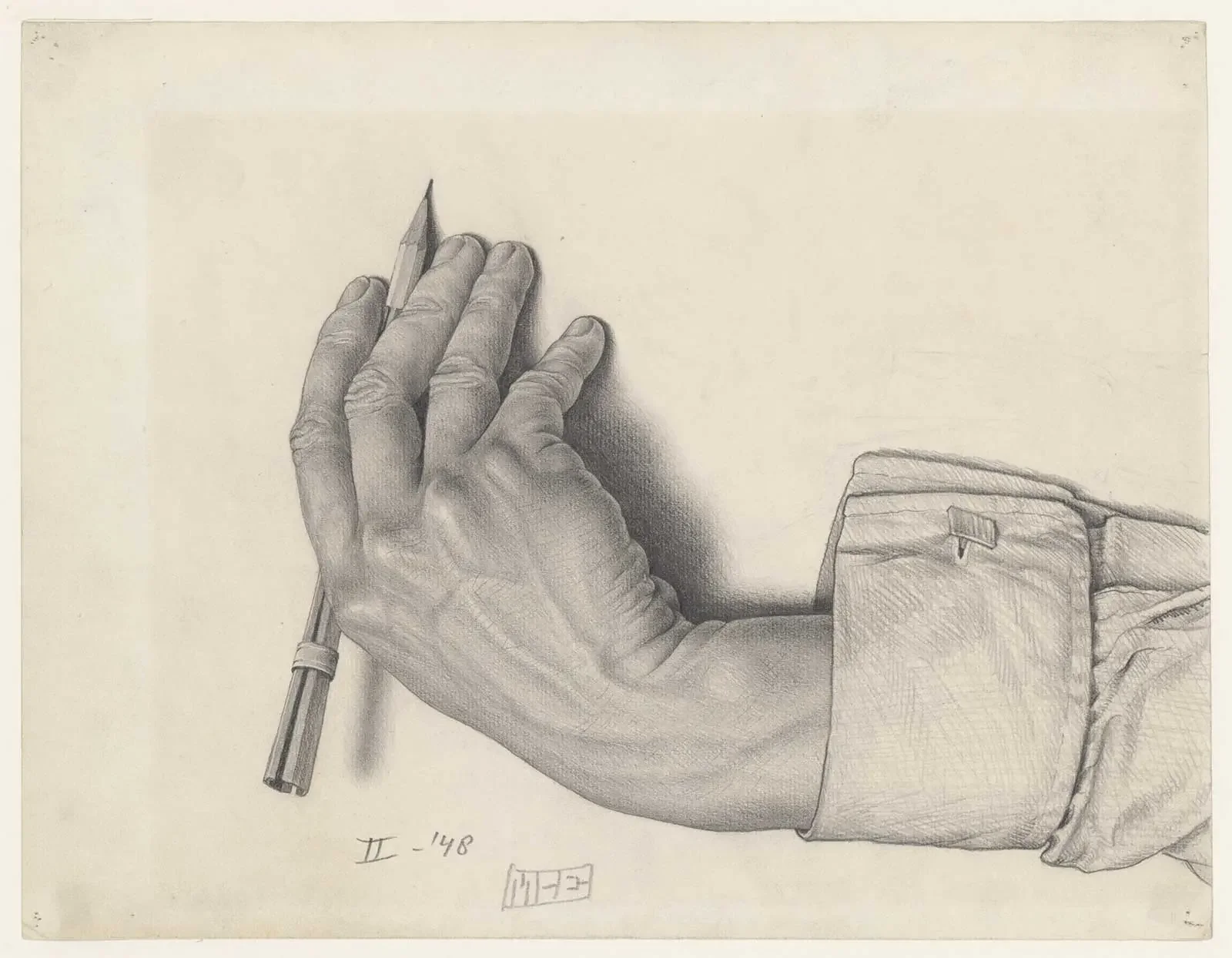

An early draft of Drawing Hands from the same year. Lithograph.

What is the meaning of Drawing Hands?

Interpretations vary, but many see Drawing Hands as a meditation on the self-referential loop, a concept that delights both mathematics and philosophy. The hands depend on each other for existence, yet neither can be said to have come first. The result is an impossible cycle with no clear origin.

Some art historians connect it to the idea of the strange loop, a term later popularized by cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter to describe systems that turn back on themselves, such as Gödel’s incompleteness theorems or Escher’s own infinite staircases. Others interpret it as a comment on the creative process: the artist shapes the work, but the work also shapes the artist.

Escher himself was famously coy about offering definitive meanings for his images, preferring viewers to puzzle them out. Still, his notebooks and letters reveal a fascination with the act of drawing as a form of reality-making, something Drawing Hands captures literally.

Was M.C. Escher left-handed?

Escher was born left-handed, but like many children in early 20th-century Europe, he was forced in school to learn to write with his right hand. The result was that he developed a rare ambidexterity, able to draw, carve, and etch with either hand. His teacher and mentor, Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita, was also ambidextrous — a coincidence that likely reinforced Escher’s comfort with shifting fluidly between left and right.

This dual dexterity shaped more than just his technique. It resonated with the deeper themes of balance, inversion, and symmetry that run through his art. In Drawing Hands (1948), one hand holds the pencil in a right-handed grip, while the other mirrors it in a left-handed pose. Rather than a mistake or hidden clue about Escher’s dominant hand, it’s best understood as a self-aware metaphor: two hands creating each other, neither one fixed as dominant.

Seen in this light, Escher’s ambidexterity wasn’t just a personal quirk. It embodied the very logic of his work, the refusal to choose one perspective, the delight in mirroring opposites, and the ability to hold contradictions in perfect tension.

An early draft of Drawing Hands, in which Escher draws a right hand. Lithograph.

A self-portrait from 1950, in which Escher draws with his left hand. Woodcut.

Why are the hands drawing each other?

The motif of objects creating each other appears throughout Escher’s work, but Drawing Hands is one of his clearest expressions of it. In everyday life, cause and effect flow in one direction: A creates B. In Drawing Hands, cause and effect are locked in a feedback loop: A creates B, which simultaneously creates A.

This mutual creation mirrors the way Escher often played with “closed systems,” where every part depends on every other. It’s the same underlying principle as his never-ending waterfalls or tessellations that loop back into themselves.

How big is Drawing Hands?

The lithograph measures 28.2 × 33.2 cm (about 11.1 × 13.1 inches). It’s a relatively small work, designed for close inspection. The compact size adds to the intimate feel: you can almost imagine the hands hovering just above your own desk, mid-sketch.

Where can you see Drawing Hands today?

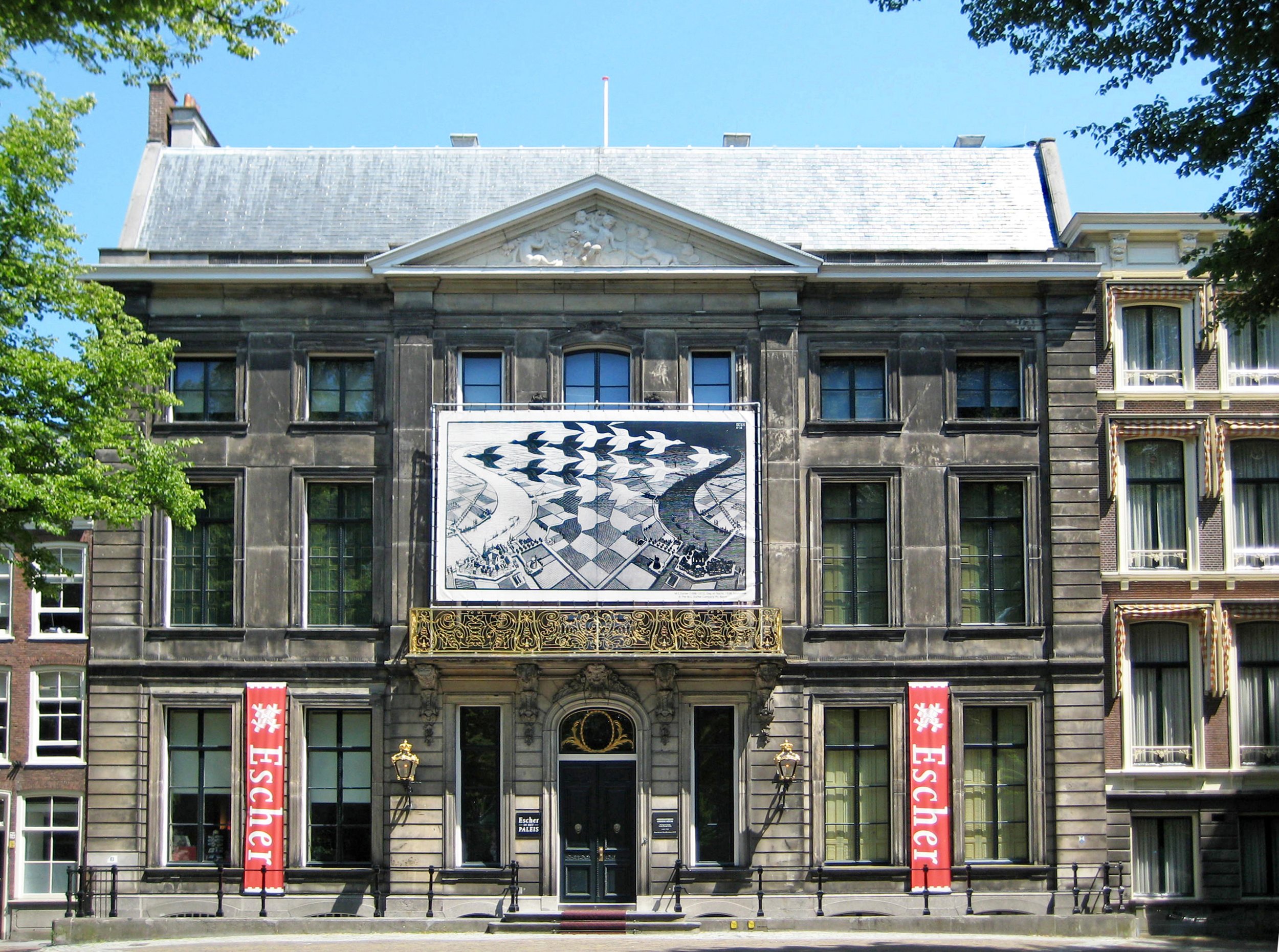

Original impressions of Drawing Hands are prized holdings in major collections. The most accessible is at Escher in Het Paleis in The Hague, where visitors can see it up close as part of the permanent exhibition. Other impressions surface occasionally at international auctions, often drawing intense bidding from collectors.

Encountering the work in person is a very different experience from seeing it in print or online. At its modest scale, the lithograph reveals an extraordinary delicacy: fine gradations of tone, the crispness of the pencil lines Escher imitated in stone, and the almost eerie illusion of hands emerging from flat paper. These subtleties often disappear in reproductions but become immediately apparent when you stand before the original.

Escher in het Paleis in The Hague.

Reptiles are a frequent subject of Escher’s tessellations.

Lithograph.

What is the Escher theory?

There isn’t a single “Escher theory” in the sense of a formal doctrine, but the term is sometimes used informally to describe the set of artistic and mathematical principles that underpin his work: self-reference, symmetry, perspective distortion, and the transformation of shapes through space.

Mathematicians admire Escher for his practical grasp of concepts like tessellation, topology, and infinity, ideas he often discovered independently, then confirmed in conversations with mathematicians such as H.S.M. Coxeter and Roger Penrose. Drawing Hands fits squarely into this “theory” by turning a self-referential idea into a tangible image.

Why Drawing Hands still resonates

More than 75 years after its creation, Drawing Hands continues to fascinate because it operates on multiple levels at once:

Artists see in it a sly commentary on the act of creation itself, the paradox of the maker being both inside and outside the work, shaping it while also being shaped by it.

Mathematicians recognize it as a visual metaphor for self-contained systems, akin to Gödel’s incompleteness or feedback loops in logic, where an object defines itself in terms of itself.

Philosophers interpret it as a meditation on selfhood and recursion: a being that only exists through its own act of becoming, a mirror of the question ‘‘Who creates the creator?’’

Casual viewers are captivated by the sheer cleverness of the illusion, the thrill of seeing something impossible rendered with absolute precision.

Its cultural afterlife has only grown. The image is endlessly reproduced and remixed: on posters and book covers, in classrooms as a thought experiment, and now in the digital age, as a metaphor for artificial intelligence, where algorithms “train” or “generate” themselves in feedback loops that feel uncannily like Escher’s two hands bringing each other into existence.

What makes Drawing Hands endure is this capacity to meet people wherever they are, as puzzle, joke, paradox, or profound inquiry. It’s a single drawing that speaks in multiple registers, refusing to settle on one meaning, much like Escher himself.