The Major Works of M.C. Escher

M.C. Escher (1898–1972) is one of the most recognizable artists of the twentieth century. Known for his impossible architectures, mind-bending tessellations, and visual paradoxes, he created prints that are as admired by mathematicians as they are by art lovers. His work is instantly recognizable: precise, black-and-white, and filled with tricks that challenge how we see the world.

Over the course of his career, Escher produced hundreds of woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints. But a handful of pieces stand out as his most famous and influential. Below, we’ll explore the major works of M.C. Escher, the prints that define his legacy.

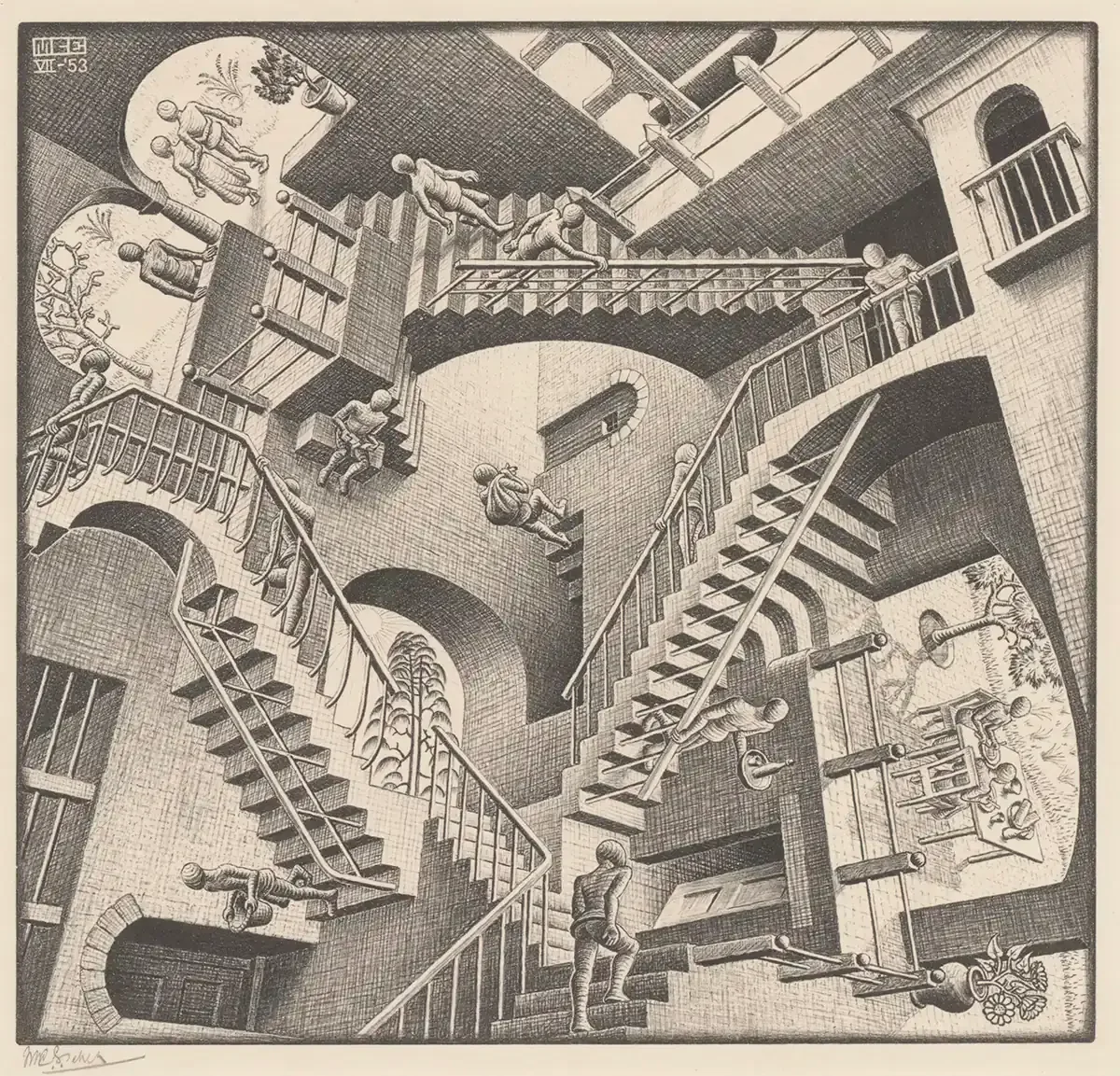

Relativity (1953)

Perhaps Escher’s most famous image, Relativity depicts a world where the normal rules of gravity do not apply. Stairs lead in every direction; figures walk sideways, upside down, and at impossible angles. At first the scene looks architectural, but closer inspection reveals a paradoxical world where multiple realities coexist.

Relativity encapsulates Escher’s fascination with perspective and impossible constructions. It also reflects his ability to make the bizarre feel orderly: every line is precise, every plane carefully shaded, even as the whole composition defies physical law. For many, this print is the defining image of Escher’s genius.

Want to read more about Relativity? You can find a the full article here.

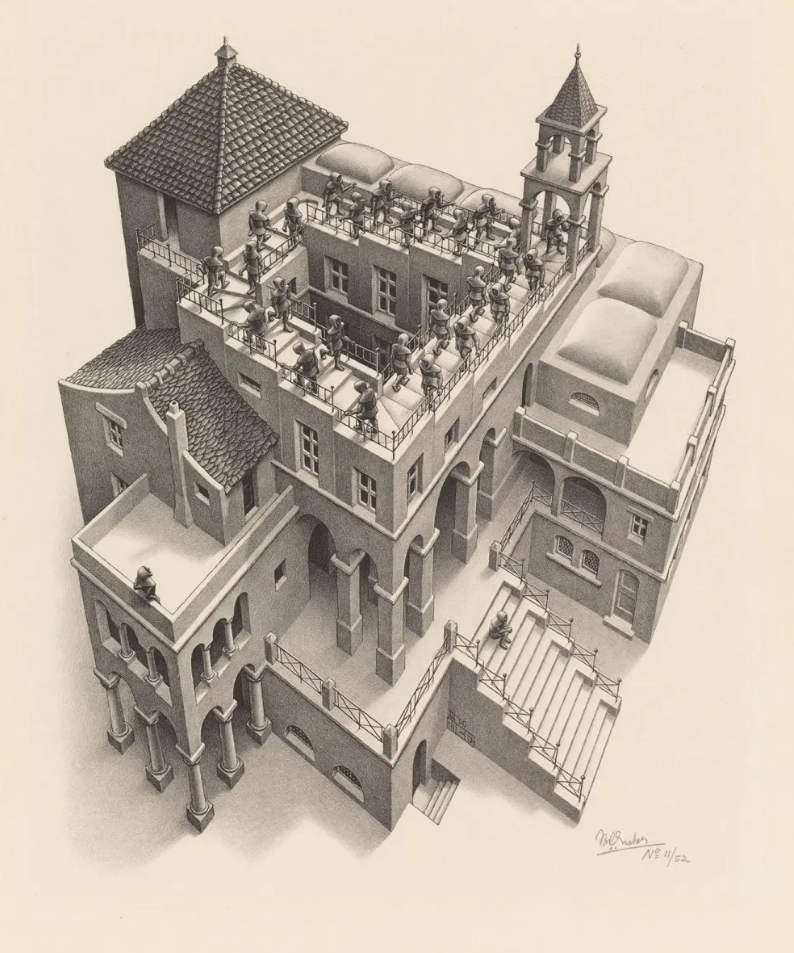

Ascending and Descending (1960)

Like Relativity, Ascending and Descending is a study of impossible architecture. The lithograph shows rows of figures walking endlessly on a staircase that loops back onto itself. Some climb, some descend, but none ever reach a higher or lower level.

Escher based the design on a mathematical discovery by Lionel and Roger Penrose — the so-called “Penrose stairs.” The result is an endless cycle, a visual paradox that embodies futility. The figures march on mechanically, trapped in a system that looks orderly but leads nowhere. It is Escher at his most philosophical, turning geometry into allegory.

Drawing Hands (1948)

One of Escher’s most reproduced prints, Drawing Hands shows two hands emerging from a sheet of paper, each sketching the other into existence. The result is a closed loop: hand A exists because hand B draws it, and hand B exists because hand A draws it.

This image has become a cultural icon, referenced in philosophy, literature, and even computer science. It represents recursion, self-reference, and the paradox of creation. Beyond its symbolic meaning, it is also technically brilliant: the shading of the cuffs, the perspective of the paper, and the realism of the hands make the illusion all the more convincing.

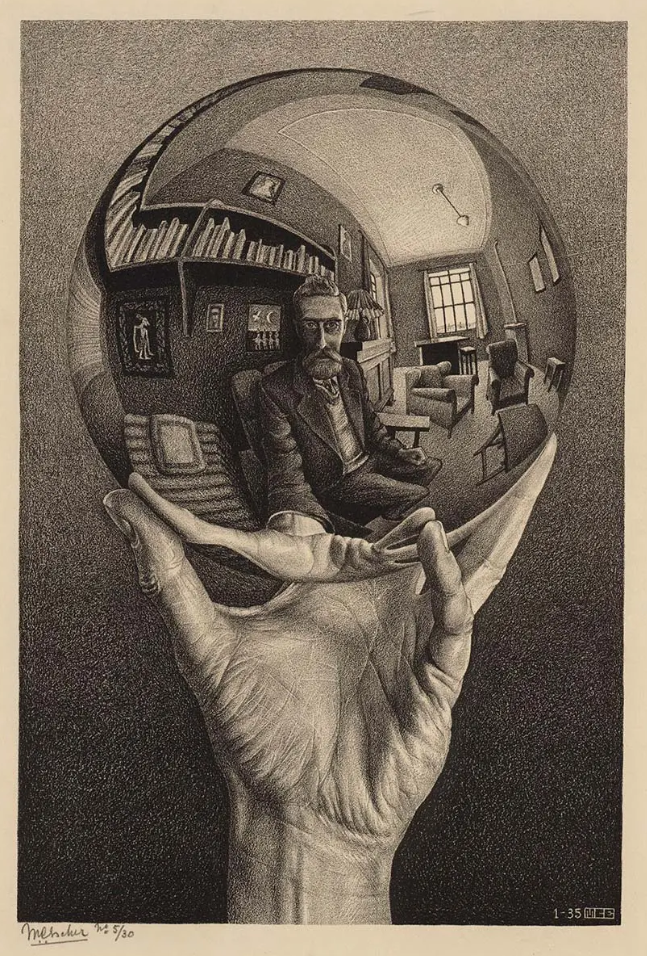

Hand with Reflecting Sphere (1935)

One of Escher’s best-known self-portraits, Hand with Reflecting Sphere shows the artist himself reflected in a glass ball. In the sphere we see the room around him, distorted by the curve of the glass, with Escher seated at its center holding the ball in his hand.

This work captures Escher’s love of reflection, distortion, and self-reference. It is also personal: we see the artist’s face, his studio, and his world, all contained within a single, fragile sphere. Like much of his work, it is both intimate and philosophical.

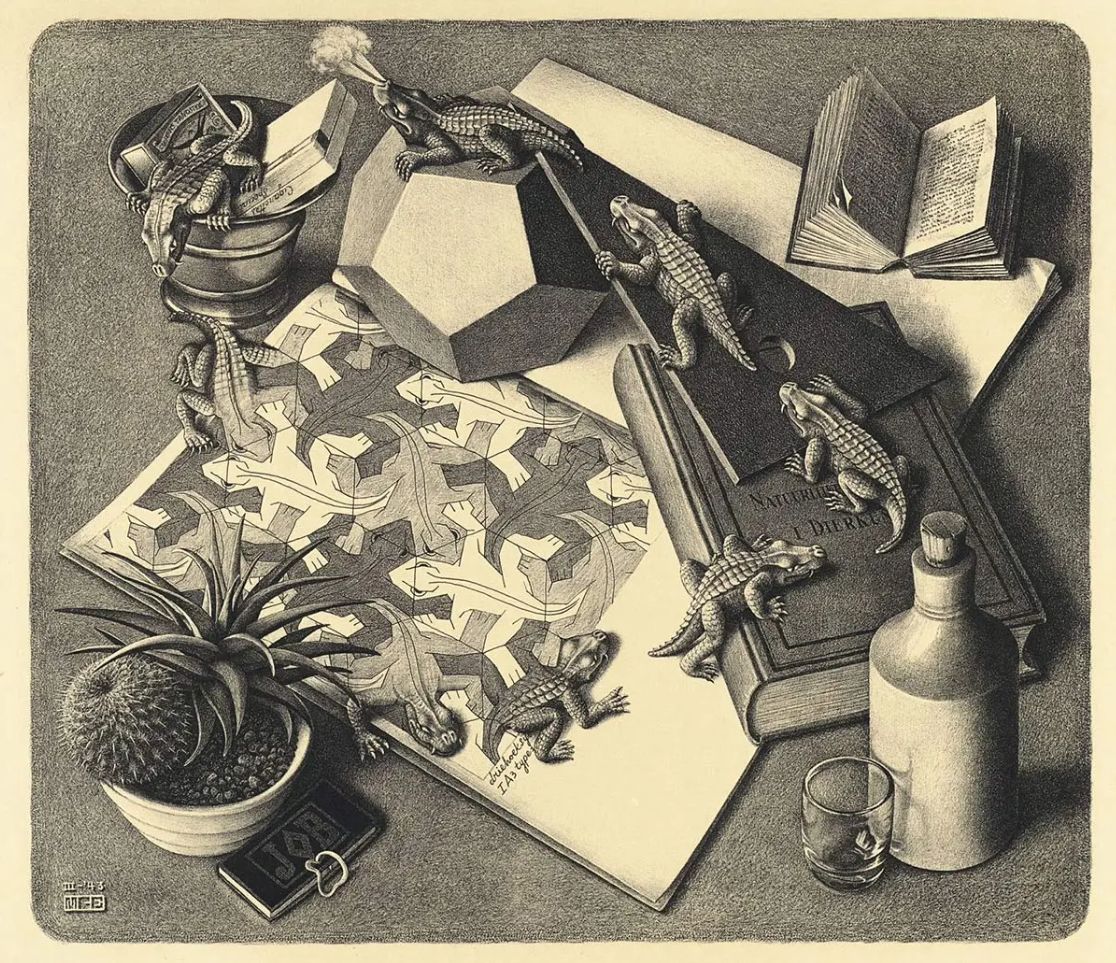

Reptiles (1943)

In Reptiles, Escher combined his tessellation studies with humor and a surreal twist. On a desk cluttered with books and objects, a tessellated drawing of lizards lies flat on the page. From it, several reptiles crawl into three-dimensional space, march across the desk, and then re-enter the drawing.

The print is often read as a meditation on the relationship between art and reality. It is also simply playful — a witty joke about drawings coming to life. Its clarity and charm have made it one of Escher’s most beloved works, frequently reproduced and instantly recognizable.

Bond of Union (1956)

Bond of Union is one of Escher’s most poetic works. Two human heads, formed from a single ribbon that spirals into space, face each other. The gaps between the coils suggest both separation and connection, individuality and unity.

This print is often interpreted as a meditation on human relationships. Unlike his more architectural works, Bond of Union is intimate and almost tender, using illusion not to disorient but to suggest interconnection.

Waterfall (1961)

Waterfall is one of Escher’s most ingenious illusions. In the lithograph, water flows uphill before cascading down a waterfall, turning a waterwheel that powers the impossible cycle. The structure is carefully constructed from two Penrose triangles, geometric figures that create the illusion of a perpetually rising path.

The image is not only visually stunning but also philosophically unsettling. It suggests a perpetual motion machine — something that cannot exist in reality. Like much of Escher’s work, Waterfall uses the language of architecture to demonstrate the limits of perception and the paradoxes of infinity.

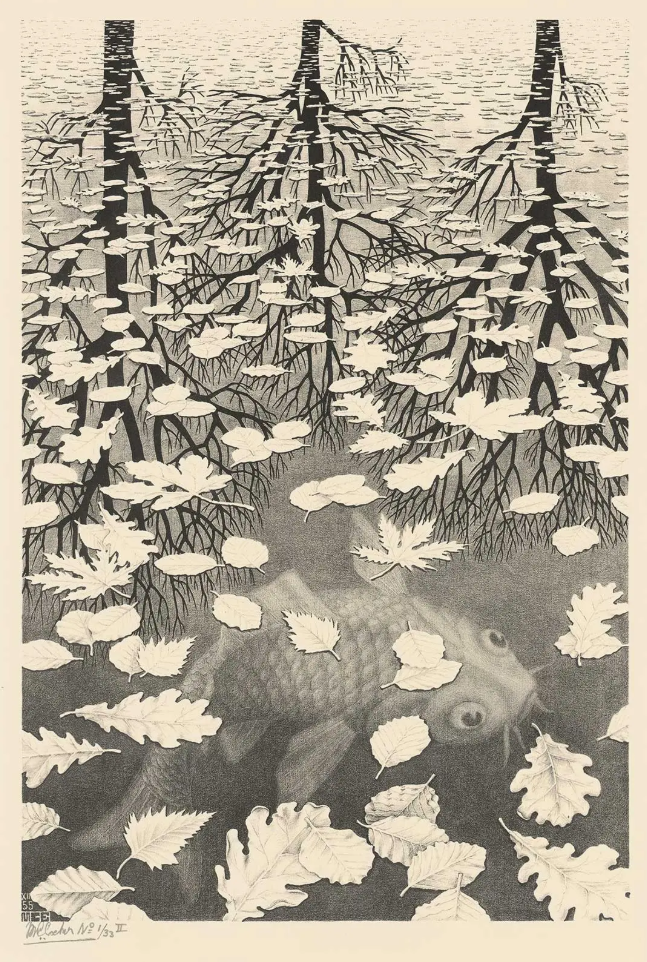

Three Worlds (1955)

Three Worlds is a quieter work, but no less profound. The print shows the surface of a pond in autumn. On the water float fallen leaves; beneath the surface swim fish; and reflected on the surface are the bare branches of trees above. Three distinct worlds, sky, water, and underwater, coexist in a single image.

This mezzotint demonstrates Escher’s mastery of tonal shading and his sensitivity to nature. It is not an impossible structure but a meditation on perspective and the complexity of seeing. The work reminds us that even the simplest scene can contain multiple layers of reality.

Eye (1946)

In Eye, Escher presents an extreme close-up of a human eye, rendered in meticulous detail. Reflected in the pupil, however, is something startling: a human skull. The juxtaposition turns the eye into a mirror of mortality, a reminder of death lurking within life.

The print demonstrates Escher’s skill as a draftsman and his interest in symbolism. Unlike his tessellations or impossible structures, this work is direct, almost confrontational, forcing the viewer to confront the fragility of existence.

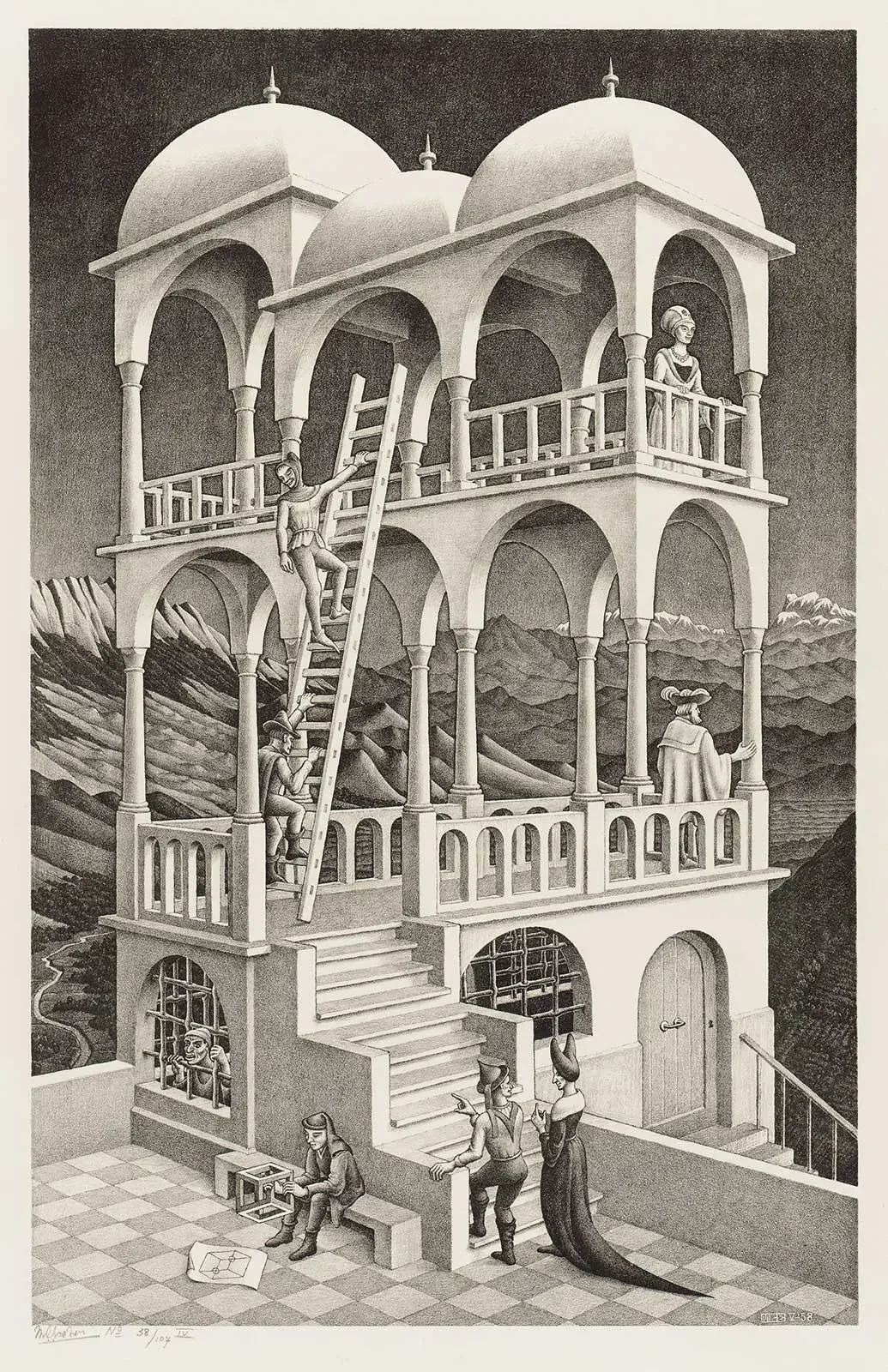

Belvedere (1958)

In Belvedere, Escher presents a building that at first appears logical but collapses under closer scrutiny. Figures climb and descend its steps, peer out from balconies, and interact with the impossible structure. The lower level is consistent, but the upper floor twists into an architectural paradox.

At the foot of the building sits a man holding a model of a three-dimensional cube, a shape that itself cannot exist. The print is a commentary on illusion and perception, showing how easily our sense of space can be manipulated.

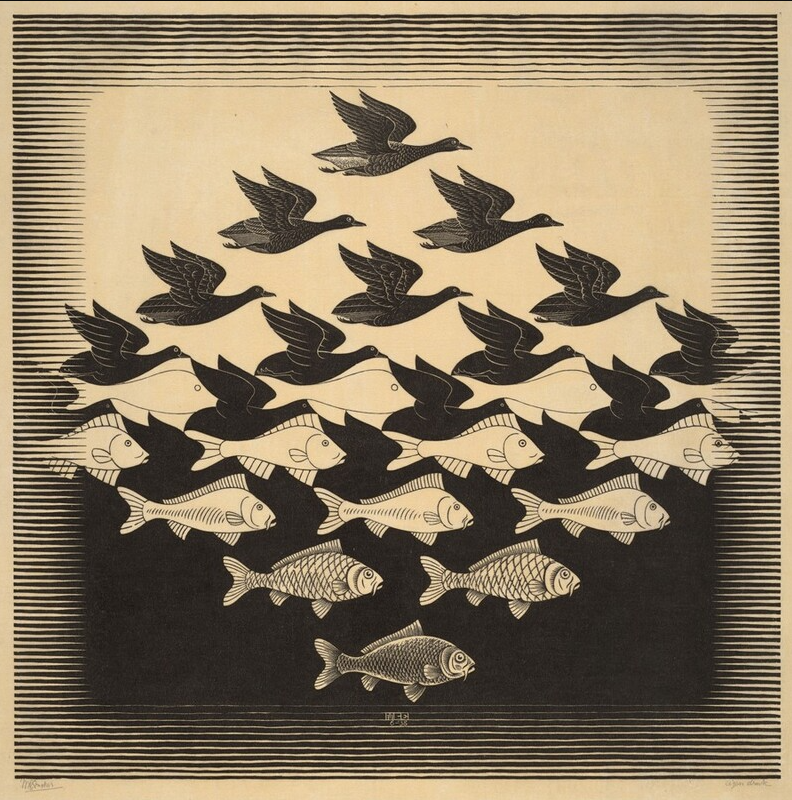

Sky and Water I (1938)

This woodcut is one of Escher’s purest explorations of tessellation and metamorphosis. Fish swim at the bottom of the page; birds fly at the top. Between them, fish gradually transform into birds, the black of one becoming the background of the other.

Sky and Water I is a perfect example of Escher’s fascination with positive and negative space, symmetry, and transformation. It is also among his most reproduced works, often used to introduce students to the concept of tessellation. Its elegance and clarity make it a cornerstone of his career.

Find a full breakdown here.

Metamorphosis I, 1937. Woodcut, printed in two parts.

Metamorphosis (1937–1968)

Metamorphosis was not a single print but a series of long woodcuts Escher created over several decades. In them, tessellated shapes gradually transform into new figures: fish become birds, birds become buildings, buildings become abstract patterns, and so on.

These works are monumental in scope, sometimes stretching several meters in length. They embody Escher’s fascination with transformation and continuity, showing how one form can become another through a series of small, logical steps.

Self-Portrait (multiple works, 1929–1940s)

Escher returned to self-portraiture throughout his career, using it as a way to explore not only likeness but perception itself. One of his earliest self-portraits is straightforward, but later works, such as those reflected in glass spheres or distorted mirrors, reveal his fascination with how vision shapes identity.

In these portraits, Escher is both subject and observer. He presents himself as a draftsman surrounded by tools of his trade, a figure absorbed by the act of seeing. His self-portraits remind us that all of his impossible constructions began with the simple act of looking closely at the world.

The enduring power of Escher’s vision

The major works of M.C. Escher span tessellations, impossible buildings, self-portraits, and meditations on nature. What unites them all is a fascination with perception, paradox, and transformation. Whether it is the quiet reflection of Three Worlds, the humor of Reptiles, or the architectural impossibility of Relativity, each piece invites us to question how we see the world.

Escher never thought of himself as part of the mainstream art world. He once said he felt more at home among mathematicians than painters. Yet his prints continue to captivate both audiences, proving that art and mathematics are not opposites but partners.

From Sky and Water I to Hand with Reflecting Sphere, Escher’s major works endure because they are more than clever tricks. They are visual metaphors for life itself: full of order and chaos, logic and imagination, illusion and truth.