Bond of Union: M.C. Escher’s Portrait of Connection

Before continuing, please take a moment to really look at the work.

Bond of Union is one of M.C. Escher’s most celebrated and enigmatic works, created in 1956. At first glance, it is a visually arresting image of two human heads, a man and a woman, formed entirely from a single continuous ribbon, twisting in space. Look closer, and you notice that these are not anonymous faces: they are widely understood to be Escher and his wife, Jetta, intertwined in a visual metaphor for unity, love, and shared existence.

Floating around them is a constellation of perfectly shaded spheres, suspended in an undefined space. The combination of the ribboned heads and the hovering orbs creates a scene that is at once intimate and cosmic: an image of personal connection framed in the infinite.

What Is the Bond of Union?

Bond of Union is a lithograph M.C. Escher created in 1956, showing two human heads formed from a single ribbon that coils through space. The figures are widely understood to be Escher and his wife Jetta, portrayed as both separate and inseparably connected.

The work belongs to Escher’s mature period, when he was moving beyond architectural paradoxes into more philosophical themes. Lithography gave him the soft tonal range needed to model the ribbon’s curves, creating a sculptural, almost skin-like effect. Since its creation, the print has been read both as a personal double portrait and as a universal meditation on human interdependence. Escher was inspired by H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man, which he read that year.

Tryouts for Rind (1954), a work very similar to Bond of Union. Woodcuts.

Why the Bond of Union still captivates

Nearly seventy years after its creation, Bond of Union continues to resonate because it works on several levels at once. Viewers are drawn in by its technical mastery, then stay with it because the image speaks to deeper human themes.

As a technical achievement: Lithography gave Escher a tonal range that allowed the ribbon to feel sculptural, almost tangible. The shading on the spheres is so consistent that the empty background becomes a believable stage.

As a visual puzzle: The ribbon invites the eye to follow its path—looping, twisting, breaking, and rejoining. Each fold suggests continuity and interruption at once, forcing you to track how the parts make up the whole.

As a personal statement: The intertwined heads are widely seen as portraits of Escher and his wife Jetta. This autobiographical layer—rare in Escher’s work—gives the print an intimacy that sets it apart from his architectural paradoxes.

As a universal metaphor: Beyond the personal, the image captures the paradox of human connection: two lives distinct yet interdependent, suspended in a larger order represented by the spheres.

What makes Bond of Union endure is not just its cleverness or its technical beauty, but its fusion of intellect and emotion. It is a portrait, a puzzle, and a meditation at once—an image that feels both rigorously constructed and profoundly human.

Rind (1954), woodcut

What Is the Meaning of the Bond of Union?

The meaning of Bond of Union is generally understood as a meditation on human connection: two figures bound together by a single ribbon, symbolizing unity and interdependence.

Escher himself rarely gave literal explanations for his imagery, preferring viewers to find their own interpretations. However, Bond of Union is one of the few works that feels unmistakably personal. On one level, the work is about human connection, two individuals joined by an invisible but unbreakable thread. The ribbon structure suggests that their identities are interwoven; the gaps between the folds imply that no person is entirely closed off, even to the one they are closest to. On another level, the image reflects Escher’s fascination with duality and structure. The ribbon is both one object and two portraits. The space between is as important as the ribbon itself, echoing his lifelong interest in how positive and negative space interact.

The Eschers on their wedding day, 1924

What is M.C. Escher’s most famous piece of work?

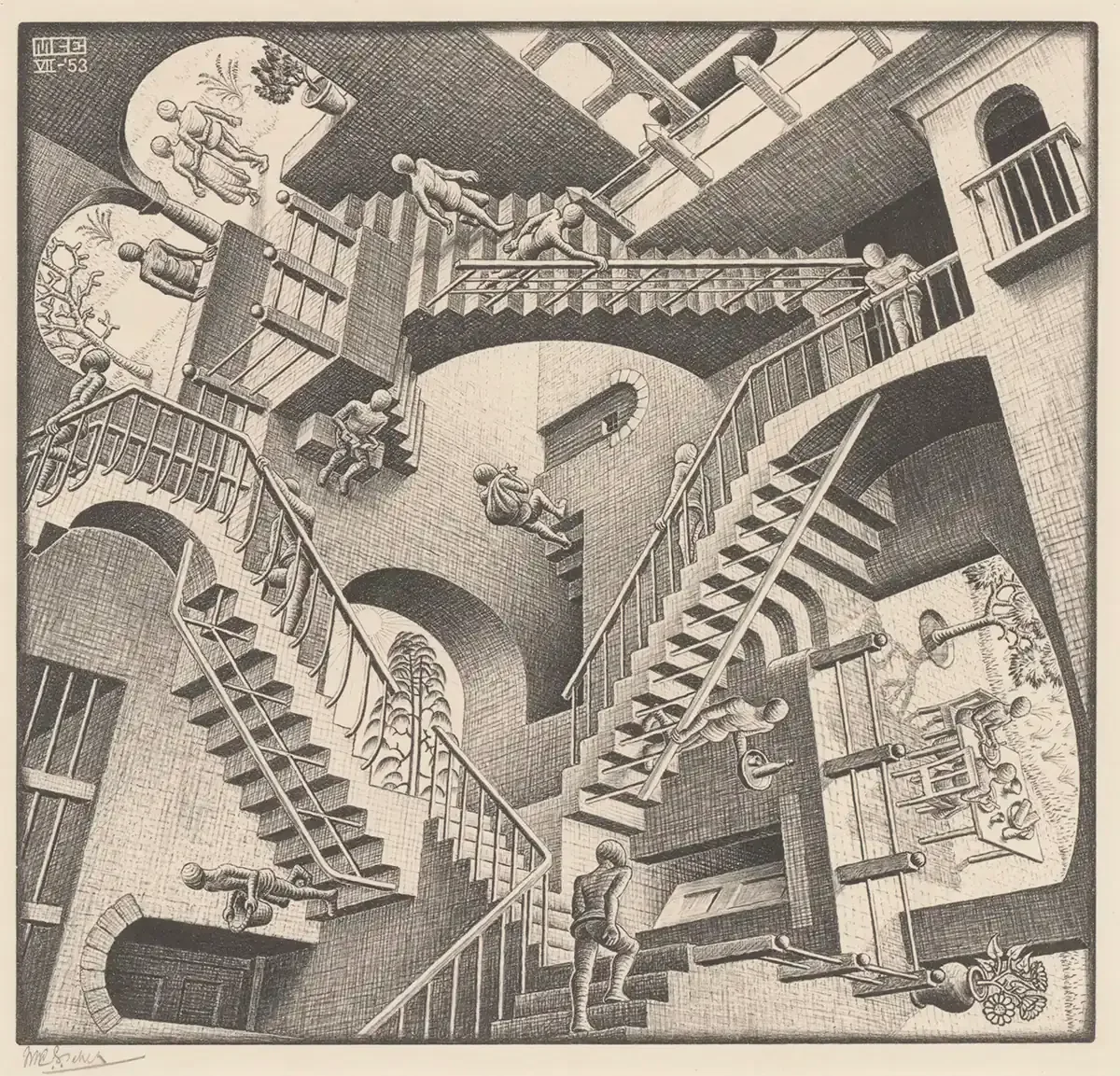

Escher is known for many iconic works, including Relativity, Drawing Hands, Hand with Reflecting Sphere, and Waterfall. Bond of Union stands out in his catalogue because it marries his technical precision with deeply personal subject matter.

While Relativity may be the single image most associated with Escher in popular culture, Bond of Union is often considered one of his most emotionally resonant works. It demonstrates that his art could be more than mathematical puzzles, it could also be a meditation on relationships, unity, and human intimacy.

What Is M.C. Escher’s Art Style?

M.C. Escher’s art style combines traditional printmaking with mathematically precise design. He worked primarily in lithography, woodcut, and wood engraving, each chosen for the effect it could deliver. With these methods, he explored tessellations, impossible constructions, transformations, reflections, and infinity. His approach was not spontaneous or dreamlike but systematic, closer to engineering than to free association.

In Bond of Union, Escher’s style appears in a distilled form:

Precision Draftsmanship: The ribbon coils with unwavering thickness and shading, each curve consistent with a single light source. This discipline creates the illusion of sculptural reality.

Mathematical Clarity: The surrounding spheres obey exact rules of lighting and perspective, establishing a coherent three-dimensional space. They are not decorative flourishes but structural anchors.

Conceptual Duality: The image reads both as a recognizable double portrait and as an abstract system of loops and gaps. This tension between realism and logic is central to Escher’s art.

Together, these qualities demonstrate why Escher is often described as a draughtsman of rules. He used the tools of printmaking not simply to reproduce images, but to build visual systems that feel inevitable once you see them.