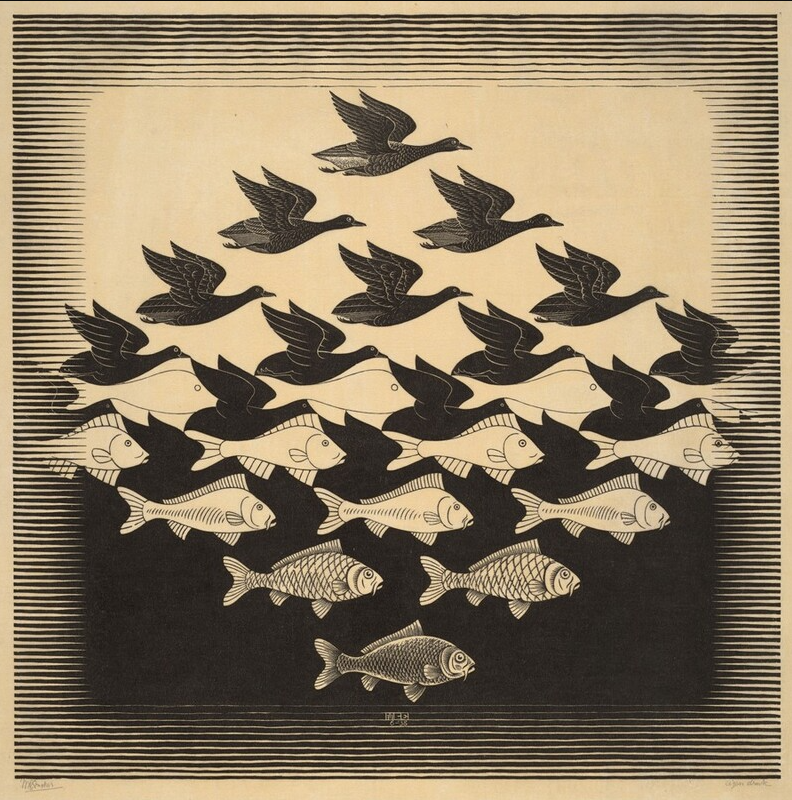

Sky and Water I: M.C. Escher’s Dance of Birds and Fish

Before continuing, please take a moment to really look at the work.

When people think of M.C. Escher’s tessellations, one image comes to mind more than any other: Sky and Water I. First published in 1938 as a woodcut print, it captures the Dutch artist’s lifelong fascination with transformation, symmetry, and the delicate balance between positive and negative space. At a glance, it looks simple: birds rising into the air, fish swimming in water, but a closer inspection reveals one of the most elegant demonstrations of Escher’s genius.

What Is Sky and Water I?

Sky and Water I is a woodcut tessellation in which birds and fish share the same space. At the bottom of the composition, rows of black fish swim horizontally across the page. At the top, rows of white birds fly in the opposite direction. Between them lies the transition: the shapes of the fish gradually shift into birds, the black of one becoming the background for the other.

What makes the print so striking is the way Escher achieves harmony between two opposing realms. The fish belong to water, the birds to sky, yet each is carved from the outline of the other. Neither dominates; they exist in perfect equilibrium. This use of interlocking positive and negative space is one of the clearest examples of Escher’s mastery of tessellation and a signature of his unique art style.

Escher also made a follow-up, Sky and Water II, in December of the same year.

Birds and Fish: A Classic Escher Pairing

Escher often used birds and fish in his art because they naturally lent themselves to tessellation. Their bodies could be simplified into basic shapes — fins and wings forming natural diagonals — that fit together with minimal adjustment. But beyond the geometry, there was symbolism: fish and birds represented opposite elements, water and air, depth and height, the unseen and the visible. By locking them together, Escher turned natural opposites into partners.

This motif appears elsewhere in his work, but Sky and Water I crystallized it in its purest form. Later pieces such as Sky and Water II and Metamorphosis II would expand on the same idea, yet none have the same clarity and balance as the original.

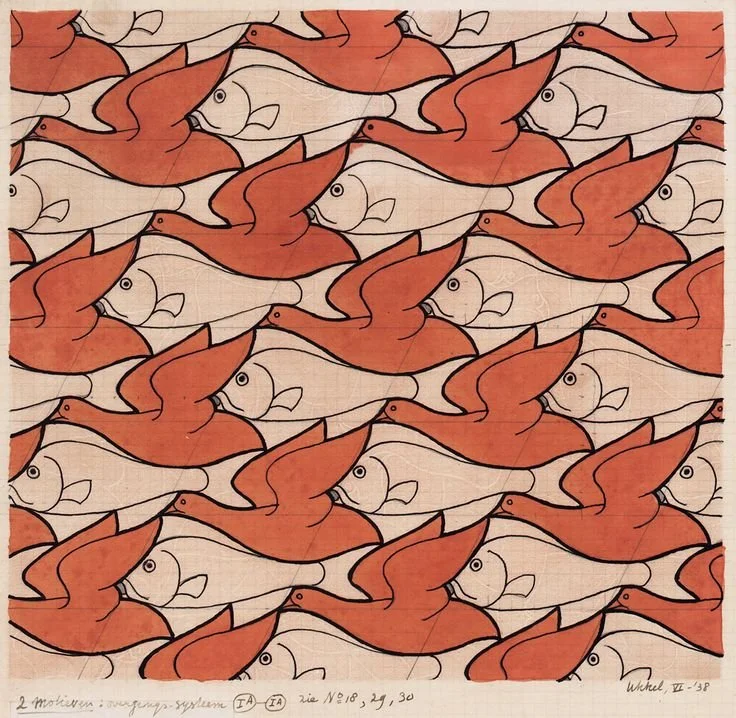

1938 was a real year of fish and birds for Escher, as they also featured in Regular Division of the Plane (Birds and Fish)

When Was Sky and Water I Created?

Escher created Sky and Water I in 1938, a pivotal year in his career. Having returned to the Netherlands after several years in Switzerland and Belgium, he was devoting himself fully to exploring tessellations and metamorphosis. This was the period when many of his most iconic works were made, including Day and Night and Metamorphosis.

To be specific, Escher was living in Baarn, a small town in the Netherlands, with his wife Jetta and their three sons. He had moved frequently in earlier years, spending long periods in Italy and Switzerland, and traveling extensively through Spain, but by the late 1930s, he had settled back in his homeland.

It was in Baarn that he built a studio and produced many of his most important prints. The quiet environment gave him the space to explore complex ideas without distraction. While his earlier Italian landscapes had been literal depictions of place, his Baarn years were devoted almost entirely to inner worlds of pattern and transformation.

The late 1930s were also a time of growing instability in Europe, and Escher increasingly withdrew into the inner world of his art. While political upheavals swirled around him, he was carving woodblocks of birds, fish, and landscapes that obeyed only the laws of geometry and imagination.

Escher would frequently return to the pattern of birds and fish, such as in Predestination (1951)

Is Sky and Water I Escher’s Most Famous Work?

It is certainly one of them. Ask people to name an Escher print, and many will picture either Sky and Water I or Relativity, the impossible staircase. While other works such as Drawing Hands and Hand with Reflecting Sphere are also iconic, Sky and Water I occupies a special place because it captures his tessellation experiments in their most distilled form.

For Escher himself, the work was part of a broader series, not necessarily singled out above others. But for the public, it has become shorthand for “Escher birds and fish,” reproduced in countless books, posters, and classrooms.

What is Sky and Water I a good example of?

The print is often cited as a textbook example of several key ideas in Escher’s work. First, it demonstrates tessellation with interlocking figurative forms, showing how abstract geometry can become lively creatures. Second, it illustrates metamorphosis, the gradual transformation of one figure into another. Finally, it is a clear study of positive and negative space, where the background of one figure is also the body of another.

It is important to note that the creation of Sky and Water I was not an isolated moment but part of a steady progression. Earlier experiments had shown Escher grappling with how to turn geometric shapes into recognizable figures. By 1938, he had mastered the technique, and works like Sky and Water I display that confidence.

The print also foreshadows his later masterpieces. In Metamorphosis II, entire cities emerge from tessellated birds and fish. In Circle Limit III, infinite fish swim toward the edge of a circle in hyperbolic space. But without the clean, elegant balance of Sky and Water I, those later, more complex visions might never have taken flight.

For these reasons, art historians and mathematicians alike point to Sky and Water I as one of the clearest visual explanations of Escher’s approach. It is simple enough for a student to grasp, yet profound enough to reward years of study.

A section of Metamorphosis II (1939), featuring very similar birds and fish.

Sky and Water has also spawned a wave of merchandise, such as this statue.

Collecting and Legacy

Today, Sky and Water I is one of the most sought-after Escher prints. Original woodcuts, especially those signed and numbered by the artist, command high prices at auction. For collectors, it represents both an accessible entry point into his tessellation period and one of his most iconic images.

In 2017, a self-print by Escher of Sky and Water II went for a hammer price of €19.500, whereas Sky and Water I went for an even higher price of €24.500.

Beyond the art market, its legacy is cultural. The print has been reproduced in countless textbooks, posters, and teaching materials. It appears in mathematics classrooms to demonstrate symmetry and negative space, and in art schools as a lesson in balance and design. Few works manage to straddle both worlds so seamlessly.

Conclusion

Sky and Water I endures because it is simple and profound at once. Two creatures, birds and fish, rise and fall in opposite directions, each cut from the outline of the other. It is a visual poem about balance, metamorphosis, and the hidden order of the world.

For Escher, it was one print among many, carved in a modest studio in Baarn. For us, it remains one of the clearest windows into his imagination: a place where geometry breathes, where opposites depend on each other, and where a flat page becomes infinite space.